AUGUST 30th – International Desaparecidos Day

The forced disappearance of people for political or social reasons is a crime against humanity

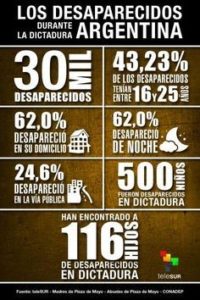

The International Day of the Desaparecidos, was established by the UN in 2010 at the proposal of the Latin American Federation of Associations of Prisoners’ Families (FEDEFAM) and other associations for human rights, to remember all those people who disappeared from one day to the next. The “forced disappearance”, better known with a term which is imposed in the whole world from Latin America in the seventies, desaparicià, is a crime against humanity, still practiced today in dozens of countries, especially Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Chechnya, Pakistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo.

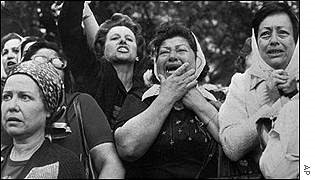

WHO DOES NOT REMEMBER THE MOTHERS OF PLAZA DE MAYO WHO DEMANDED TRUTH AND JUSTICE FOR THEIR “MISSING” DAUGHTERS AND SONS? The Organization was created by the mothers of Argentinean dissidents who disappeared under the military dictatorship between 1976 and 1983 and takes its name from the square in Buenos Aires, which since the 1970s has become the usual meeting place for women, every Thursday, to remember their children.

WHO DOES NOT REMEMBER THE MOTHERS OF PLAZA DE MAYO WHO DEMANDED TRUTH AND JUSTICE FOR THEIR “MISSING” DAUGHTERS AND SONS? The Organization was created by the mothers of Argentinean dissidents who disappeared under the military dictatorship between 1976 and 1983 and takes its name from the square in Buenos Aires, which since the 1970s has become the usual meeting place for women, every Thursday, to remember their children.

It all began on April 30, 1977 when a group of fifteen women, led by Azucena Villaflor, gathered in front of Casa Rosada to ask the military junta, which had overthrown the Péron government and established the dictatorship, to release their children. The response of Videla’s regime was not long in coming: Azucena Villaflor was kidnapped in December 1977 and she was never heard again. Some say that she was imprisoned in the ESMA prison camp, the Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada, where she was tortured and then killed. Perhaps her body was one of many that were taken, put on a plane and thrown from the so-called “flights of death”. The disappearance of Azucela Villaflor did not stop the battle of the Mothers that continued even after the establishment of a democratic state in 1983.

At first the mothers demanded the release of their children and later they demanded that those responsible be held accountable for their death before the courts. They called them crazy, terrorists, witches, distorted beasts:

“We were called the crazy ones, and someone thought it was an insult. They put us in every Thursday, and we would come back. They told us, there they were, the crazy ladies. We arrest them and they come back. But we knew that we were crazy with love, crazy with the desire to find our children…and then, why not? A little bit of madness is important in order to fight. We have overturned the meaning of the insult of those murderers”. (Madres de Plaza de Mayo, 1997)

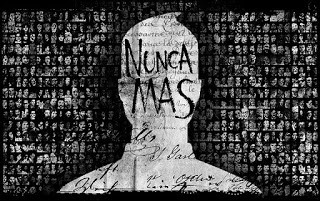

The “enforced disappearance” is a multiple violation of human rights that lasts over time: of those who disappeared after the arrest and their families, who wait in vain, for years, not so much for their return as a minimal bit of news, a subtle confirmation that they are alive or dead. The waiting for years and years in this situation of uncertainty leads to the horror of the “disappearances” such as to associate, sometimes, to the confirmation of the discovery of a body, an expression of relief: you can mourn, celebrate a funeral, have a tomb to pray on and bring flowers, try to take back your life, or what remains of it, as an orphan or widow.

Uncertainty is more hostile than death.

Death, though vast,

is only death and cannot grow.

There is no limit to uncertainty,

perishes to rise again

and die again,

is the union of nothingness

with immortality.

(Emily Dickinson)