Calls to action to make life thrive/3

Calls to action to make life thrive/3

By the Editorial Board

The coming days will bring to maturity the hopes and efforts of two intense journeys taken over the last few years and which will soon converge more directly with the birth of the new Southern Europe region[1]: one carried out together with the sisters and partners-in-mission in Portugal and Spain; the other, even more choral, with the Congregation that guided us in the evolution toward the new governance model[2].

We live in a time of “letting go and letting come,” which is why the newly formed New Directions Committee pushes us to “journeys” that include “structural and spiritual components,”[3] serving a lost humanity that “needs a supplement of soul so that it becomes more human”[4].

These “journeys” invite us to take the path “less trodden,”[5] that of integration, that is, of the weaving between structures of governance and human growth, between organization and communion, through new levels of engagement on the part of all partners-in-mission to fulfill the mission in the region[6]…trusting in the grace of transformation[7].

governance and human growth, between organization and communion, through new levels of engagement on the part of all partners-in-mission to fulfill the mission in the region[6]…trusting in the grace of transformation[7].

The Congregation’s new governance structure – resulting from the long participatory discernment led by the Life Researchers group first and the New Directions Committee today – seems especially valuable to us because “no one pours new wine into old wineskins. Otherwise, the wine will burst the skins, and both the wine and the wineskins will be ruined. No, they pour new wine into new wineskins” (Mark 2:22).

With new wineskins, the new governance structure, the Congregation wants to address the need for leadership among vowed members and to promote the full engagement of partners-in-mission[8] offering a way to work and plan together now, rather than waiting until current structures prove themselves unviable[9].

With new wineskins, the new governance structure, the Congregation wants to address the need for leadership among vowed members and to promote the full engagement of partners-in-mission[8] offering a way to work and plan together now, rather than waiting until current structures prove themselves unviable[9].

The goal of strengthening the leadership among vowed members in order to give continuity to the charism and to make the mission sustainable, perhaps also expresses the Congregation’s commitment, in a time of true spiritual bankruptcy[10], to go against the tide with respect to the crisis of consecrated life. This way of life has always been part of the Church, marking its essential steps through history. One need only think of what the following events have meant for the Church and society:

the mission sustainable, perhaps also expresses the Congregation’s commitment, in a time of true spiritual bankruptcy[10], to go against the tide with respect to the crisis of consecrated life. This way of life has always been part of the Church, marking its essential steps through history. One need only think of what the following events have meant for the Church and society:

– the Benedictines at the time of the barbarian invasions;

– the mendicant orders and St. Francis in the Middle Ages;

– St. Ignatius and the clerical orders during the Age of Discovery;

– St. Vincent de Paul in the 1600s for the spiritual renewal of the Church and dedication to the poor;

– the flowering of Institutes, including our own, from the 1800s onward.

Even when it was defined in the terms of fuga mundi, consecrated life was in fact felt to be very concretely present and significant, and  for this reason it has deeply marked the journey of the people of God. Today, things have changed. And it is not just a problem for consecrated life: it is the Church itself that has to come to terms with change and secularization and all that goes with it. We are at a turning point in humankind, “a moment compared to which the transition from the Middle Ages to modern times seems almost insignificant.”[11] This is how the future Pope Benedict, back in 1969, expressed his vision of the crisis of the Church in the West and the future that awaited it: it will have to start more or less from the beginning, to live a new beginning!

for this reason it has deeply marked the journey of the people of God. Today, things have changed. And it is not just a problem for consecrated life: it is the Church itself that has to come to terms with change and secularization and all that goes with it. We are at a turning point in humankind, “a moment compared to which the transition from the Middle Ages to modern times seems almost insignificant.”[11] This is how the future Pope Benedict, back in 1969, expressed his vision of the crisis of the Church in the West and the future that awaited it: it will have to start more or less from the beginning, to live a new beginning!

Pope Francis shared and made his own the predecessor’s prophecy about the future of the Church in the West, whose survival under the blows of galloping secularization, he said, would depend on the strength of creative minorities. Somewhat like what happened in the first centuries of Christianity[12].

centuries of Christianity[12].

“Pope Benedict was a prophet of this Church of the future, a Church that will become smaller, lose many privileges, be more humble and authentic and find energy for the essential. It will be a Church that is more spiritual, poorer, and less political: a Church of the little ones. As a bishop, Benedict had said: let us prepare ourselves to be a smaller Church. This is one of his most profound intuitions”[13].

We know very well that Pope Francis loves the “zero point” Churches: “There is a hidden grace in being a small Church, a little flock,” he said in Kazakhstan. It consists in the perception of not being “self-sufficient,” of finding oneself “lacking.”

The Church of the future envisioned by Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis – as well as for the future of our Congregation as described in  the Direction Statement – acknowledges its own “non-self-sufficiency” that requires a “new beginning” open to new relational logics aimed at strengthening cooperation, co-responsibility, complementarity and interdependence: “We recall that the purpose of the Synod is to plant dreams, draw forth prophecies and visions, allow hope to flourish, inspire trust, bind up wounds, weave together relationships, awaken a dawn of hope, learn from one another and create a bright resourcefulness that will enlighten minds, warm hearts, give strength to our hands”[14].

the Direction Statement – acknowledges its own “non-self-sufficiency” that requires a “new beginning” open to new relational logics aimed at strengthening cooperation, co-responsibility, complementarity and interdependence: “We recall that the purpose of the Synod is to plant dreams, draw forth prophecies and visions, allow hope to flourish, inspire trust, bind up wounds, weave together relationships, awaken a dawn of hope, learn from one another and create a bright resourcefulness that will enlighten minds, warm hearts, give strength to our hands”[14].

There is an extraordinary convergence between the paths initiated in the Congregation and the path of the Synod: the desire for the infinite that connects them results in paths of radical transformation, in processes of spiritual liberation to illuminate our  future commitments. From our “new beginning,” sealed with the establishment of the Southern Europe region, may creative activity and more bonds of reciprocity flourish to “respond more urgently to the cry of our wounded world,”[15] more co-bound,

future commitments. From our “new beginning,” sealed with the establishment of the Southern Europe region, may creative activity and more bonds of reciprocity flourish to “respond more urgently to the cry of our wounded world,”[15] more co-bound,

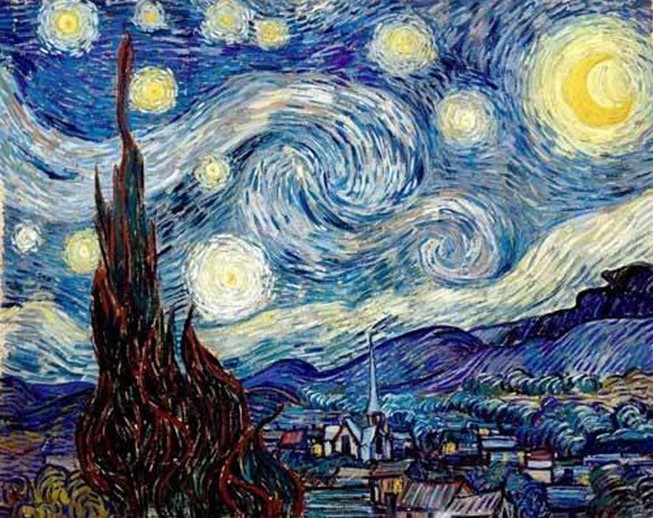

more spiritually free. It will be like going out at night to paint the stars[16]:

“Not from poverty and misery, but from surplus wealth and well-being;

not from our deficiencies, but from our consumption, in which we ultimately consume ourselves […]

not a liberation from our helplessness, but from our excess of power;

not a liberation from our pain, but from our apathy”[17]

[1] See Annex A Implementation Process of the new governance by the New Directions Committee.

[2] See Annex A Implementation Process of the new governance.

[3] See Annex A Implementation Process of the new governance.

[4] An urgency recalled in the opening speech of the 1999 Synod for Europe, but reaffirmed in the present day.

[5] From the poem The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost (1874-1963), John Kennedy’s most beloved American poet.

[6] See Appendix E to the “Regional Enlarged Leadership Team (RELT)” section.

[7] See Direction Statement of the 30th Congregational Chapter.

[8] See Direction Statement of the 30th Congregational Chapter, section A: NEW GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE, p. 4.

[9] Ibidem.

[10] This is how Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk who died in 1968, shed light on the deep crisis the whole West is experiencing. Today, the “bankruptcy” does not only concern the sphere of religion, since the spiritual constitutes an ethical-anthropological axis and concerns everything that transcends the self and that man experiences as the striving toward an ideal of authenticity always yearned for and never actually reached.

[11] From the radio talks that the future Pope Benedict had held in 1969 on the future of the Church.

[12] This is Father Antonio Spadaro’s effective image about the logic of the Pontiff’s evangelical proclamation.

[13] Pope Francis during his conversation with Malta’s Jesuits during his visit to Malta in April 2022.

[14] See Preparatory Document of the Synod of Bishops.

[15] See 30th General Chapter.

[16] So wrote Van Gogh to his brother at a particularly difficult time in his life when he painted The Starry Night: “When I have a terrible need of – shall I say the word – religion. Then I go out and paint the stars.”

[17] See Johann B. Metz, Mystik der offenen Augen: Wenn Spiritualität aufbricht, 2013.