Group violence in Milan on New Year’s Eve: ‘second generations’ in disarray and failures of coexistence between Italians and foreigners in Italy

2 young people arrested, 18 searched and the first 12 investigated for the violence in Piazza Duomo, both Italians and foreigners. The two arrested are ‘second generation Italians’, i.e. members of families from North Africa (one of Egyptian origin, living in Turin, and the other from Morocco, living in the hinterland of Milan). According to the Milan Public Prosecutor’s Office, they are the authors of ‘almost complete sexual violence accompanied by robberies of mobile phones and handbags’.

Photo: La Repubblica

“I screamed looking for my friend, I climbed up a low wall to spot her but lost sight of her. In the meantime the police arrived with shields and batons. The group disappeared, my friend was there, trying to cover herself with her jacket tight over her chest, she had no clothes on, no bra, no panties, huddled on the ground with bruises, her trousers down to her ankles. She was rescued by a policeman, and an ambulance took her to hospital. This is the drama of two of the victims of the New Year’s Eve violence in Piazza Duomo as told to investigators. Targeted, surrounded and abused. “She was kept lying on her stomach, lifted off the ground, other boys groped her everywhere,’ one of them adds. And again: ‘Everything around was disgusting,’ she told the deputy prosecutor Letizia Mannella and the public prosecutor Alessia Menegazzo. ‘There were many boys, whoever passed by took the liberty of putting their hands on them.

(Source: https://milano.repubblica.it)

Photo: Il fatto quotidiano

The investigative activity, based on the vision of the images of the surveillance systems, on the examination of various witnesses and of the victims themselves and, finally, on the analysis of the various social networks, led to the identification of 15 young adults and 3 minors, aged between 15 and 21 years, both foreigners and Italians of North African origin, who, for various reasons, are believed to have participated in the New Year’s Eve raids. (Source: Avvenire)

BUT WHO ARE THESE GUYS?

- An expert suggests:

“We know that they come from difficult, or problematic, urban contexts”, answers Marco Terraneo, sociologist at Bicocca, expert in immigration and deviance. “Children of Italians, children of foreigners, with uneven schooling, often interrupted. They have legitimate aspirations, but cannot access the privileges of our society”. They are excluded, marginal, and yet they would like to be protagonists of something, but this is impossible, “and social marginality makes deviance and actual crime easier”. (Source: Repubblica).

- A privileged observer – a bouncer at a well-known Milanese nightclub – looks at the phenomenon of the youth gangs that pour into the Milanese metropolis at weekends and on holidays:

“They are Italians, lots of them. And Maghrebi, and also those already born in Italy, who speak Italian very well. But so aggressive, I don’t know what they have to be like that”. They are the children of our banlieue, unhappy and bad boys, drawn like moths to the glitter of the metropolis of which they know four or five addresses: the Navigli, Corso Como, the Centrale, Piazza Duomo, where on New Year’s Eve their rage was unleashed on the nine girls, in that horrendous game of woman-hunting. They can’t go anywhere because they have no money, not even to the Rinascente to have a look, they see luxury from the outside, they imitate trappers in their clothes, but they are mostly cheap imitations of sweatshirts and caps. They would do anything to get a good pair of trainers, they despise their parents, understood as losers, slaves, who cannot give them more than they give. Workers, bricklayers, carers, often have children like this, and ethnicity has nothing to do with it. (Source: Repubblica)

WHAT ARE THEY SIGNALLING?

We are faced with the transformation of a way of gathering young people overwhelmed by the potential of the web and social networks. Today’s groups are reminiscent of the old ‘companies’ in a world that during the week meets more on the web than in person, but which often ‘aggregates’ by ethnicity and sometimes by a commonality of problems rather than interests.

New Year’s Eve in Milan gives us the responsibility to rethink the Italian model of integration in institutional, public and private networks, drawing on the critical experiences of some European countries, including Germany, France and England.

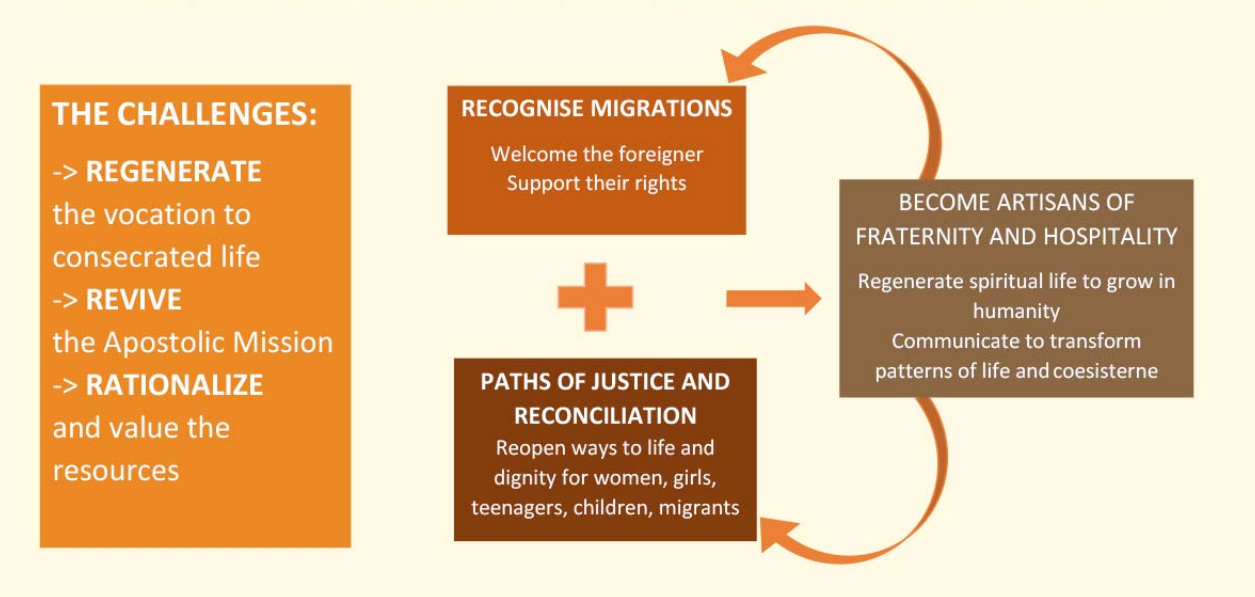

For us, the paths to a coexistence respectful of differences are outlined in the Positions of the Congregation and in the Strategic Plan of Italy-Malta Unity.