From the Spirituality Center of Angers, a look at the epidemics from the time of the Founders to today

How have communities dealt with

epidemics in the history of the congregation?

The current global health crisis is unprecedented. We, the Spiritual Center of Angers, thought it would be interesting to question ourselves. Searching through the archives, we discovered the many epidemics that have confronted the congregation's communities from the time of St. John Eudes and St. Mary Euphrasia to the present day. At a time when medical knowledge was still very limited, we wondered to what extent communities and institutions had been affected. How did the religious sisters and young people deal with these trials?

In the various correspondence, annals and letters addressed to the communities, we can identify the main epidemics and the management of these crises in the last centuries.

We propose to discover, through some examples, the problem of health crises, especially in France but also in some other countries according to the archives we have at our disposal.

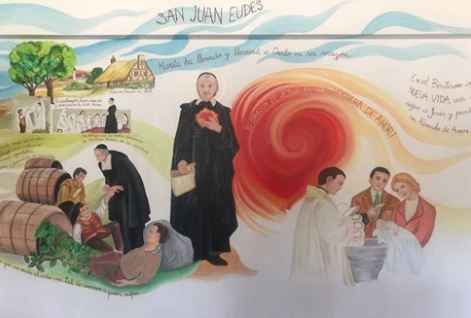

St. John Eudes helping the victims of the plagu

Shortly after his ordination in Paris, St. John requests in 1627 permission to go back to his native Normandy which is then badly affected by a plague epidemic. With the help of another priest, he goes in search of the sick in the Diocese of Séez to take their confession and bring them communion. When the epidemic resumes in 1631, he helps the sick and, in order to be closer to them and to avoid to contaminate the healthy, sleeps and eats in a barrel outside the city of Caen, in a meadow belonging to the “Abbaye aux Dames” (Ladies’ Abbey).

This is the account given by Paul Micent in his biography of St. John Eudes.

“In 1627, John Eudes was studying in Paris when he received from his father alarming news regarding his native region: the plague was restarting with renewed vigour! (…) In the last 18 months he had been a priest of Jesus, the pastor who gives his life: he had to go in the depth of destitution. (…) He was welcomed by a kind priest who gave him accommodation in his home. (…) Every morning, they both celebrated Mass and left together with John Eudes carrying consecrated Hosts in a small tinplate box around his neck (…). They went in search of the sick (…) this lasted for more than 2 months. The epidemic stopped and the young priest returned to Paris (…). When the old John Eudes wrote down these memories in his diary, he mentions the small tinplate box: ‘it is at the back of my trunk.’ Long after he preciously kept this souvenir linked to an act which had committed his existence in the service of his most wounded brothers for good.[1]”

“We often see him being close to the poor, attentive to the frequent crushing situations around him. (…) This hardship increased suddenly: a piece of news cast terror: the plague was present once more (…). It caused casualties in 1630 (…) before striking again well before the spring of 1631. As in 1627, John Eudes decided to invest himself personally. People tried to dissuade him, but he laughed and replied that he did not fear anything as he himself was meaner than this disease. (…) John Eudes wanted to assist the sick: he undertook to live similarly to those whom he assisted: they were isolated in the meadows, sheltered in large barrels: there he prayed, slept, ate. (…) Father de Répichon [Superior of the Oratory in Caen] and two other Oratorians fell ill in their turn, John Eudes came home to his sick brothers. He wanted to care for them, ‘to bring them all the physical assistance usually given to other patients’ […]. The Superior and one of the Fathers died in his arms. […] Exhausted, John Eudes fell gravely ill in his turn, people feared for his life. […] John Eudes did not die. He recovered and came out stronger from this trial! He allowed himself to be seized up to his roots by the Gospel of Jesus![2]”

Then the archives do not enable us to trace epidemics affecting the communities of Our Lady of Charity in the 17th and 18th Century. Let us be transported directly to the 19th Century, to the time of St. Mary Euphrasia.

Cholera

It is the most dreaded plague. The archives mention several severe epidemics especially in the years 1850 and 1860.

In Italy, in Turin in 1854, the epidemic caused 70 000 casualties in three days in the city according to the letter of the community. “The area that we live in was where cholera made the greatest number of victims. The houses around ours countered many victims, as did the quarantine station which was only a few meters away from us. Often at night our enclosure was illuminated by straw mattresses that were being burned and which had been used by the sick.[3]”

In France, the city of Bourges where the Congregation has been present for 15 years also faces an epidemic in 1854. The very day the news reaches the Motherhouse, on 2nd November, St. Mary Euphrasia sends ten Sisters from Angers to “rush to the assistance of the victims[4]” including the First Nurse and the First Pharmacist of the Motherhouse. The Foundress is even granted permission from the Prefect of the Maine-et-Loire department to use the brand new telegraph of the prefecture to inform the Sisters in Bourges of their arrival, therefore not hesitating to use the latest new technologies of the time. The First Nurse, Sr. Mary of St. John Chrysostom Royer, left an account of the evolution of the epidemic[5]: when they arrive, 28 people are gravely ill and 4 Sisters have died including the one in charge of the people in care. The doctor does not leave the patients’ bedside, and the Cardinal-Archbishop organised the transfer of many of the sick to the newly-built small seminary.

Egypt suffers from several epidemics in 1848, 1854 and 1865; the last one during the summer is particularly serious. “The cholera morbus has hit Alexandria severely since the 12th of this month, it made many casualties; we hoped that Cairo would be spared but it reached the city in the last 3 days, is increasing and violent. (…) We are following the measures prescribed given to us by the doctor, not a single fruit enters the House, we eat only meat, rice and potatoes (…).[6]” Three Sisters who treated the sick, including the Superior Sr. Mary of St. John the Evangelist, as well as five residents died. A tribute was paid to the three Sisters in a French newspaper as follows in the illustration below: “Three heroines succumbed: their names must not be ignored; they belonged to the Congregation of the Good Shepherd of Angers.[7]”

In France, in Toulon in 1884, a Sister, probably working in the infirmary, explains to the Superior of house in Annonay the treatments to provide to the sick, in view of the epidemic reaching her Community[8]. The details she gives are a proof of her experience and of the seriousness with which this plague was considered. For example, if the condition of the patient deteriorates, she recommends wrapping her “in a woollen blanket, with hot water bottles and warm bricks in order to maintain or to bring back the heat.” If the patient has cramps, the Sister recommends scrubbing the patient with, she specifies, a woollen stocking that one threads into the arm to have more strength and to facilitate the operation.” During convalescence, she pays particular attention to the diet (a fatless broth) to observe for a few days, “until the patient is able to have a small steak.[9]”

“Ways to treat the patients suffering from cholera”

Typhus and typhoid

In France, the two diseases create havoc in the years from 1830 to 1850. In 1836 in Angers, 28 Sisters are ill with typhoid, and three of them pass away during the same month: “In a few days twenty-eight patients entered the infirmary; three of our young lay Sisters succumbed in the space of five days. (…) Our good Mother, plunged into grief, lives in the infirmary, in the middle of her dear patients.[10]”

In Strasbourg in 1841, the disease is introduced in the house through a resident who is contaminated during a visit to her family. Two Sisters fall ill on 1st August, and by the 4th 12 residents are also sick. Two days later, the house registers 41 sick (five Sisters, 10 children, a Contemplative Sister and 25 residents). Four doctors work to cure what they quickly diagnose as typhoid fever: “the disease was so violent that the sick entirely lost their reason in a short time, and several became unable to speak.[11]” Following a visit from the Bishop, 15 residents are transferred, on his request and with the authorization of the Prefect, to the hospital to avoid the disease from spreading further. Seven of them die.

The authorities also take action in Reims where the epidemic breaks out in the group of the young people in care towards the end of the summer of 1856. On the doctor’s orders, the sick are sent to the hospital. But the disease continues to claim victims in the classes, and at the end of November and the beginning of December, following several visits from the civil and health authorities, two rooms of the general hospital are put at the disposal of the young patients. Moreover, the deputy prefect organizes the transfer of the 48 convalescents to a disused Carmelites convent. Five Sisters also fall ill which requires an adjustment of the management of the monastery: three Sisters are assigned to the former Carmelite convent, where “the only elements left are its four walls, a few doors as well as windows that do not close properly”, to organize the reception of the convalescents. The Touriere Sisters bring the meals. Meanwhile, some workers operate at the Good Shepherd for the necessary sanitation and repairs, to the extent that the Sisters claim that the workers are a “nuisance”; it is necessary to transfer the healthy people in care to the exterior Chapel during the day. Fortunately all the patients are cured and at the end of 1857 the situation is back to normal[12].

The disease also breaks out in the house of Our Lady of Charity in Le Mans, about 100 km from Angers, at the end of July 1857, probably as a result of clearing works in a nearby watercourse. Forty people in care fall sick, eight of them die, but the grateful Sisters report that “the number of victims would have been even greater without the admirable dedication of the gentlemen doctors[13]”. During this trial, the Sisters can count on the help of the authorities as well as of private individuals: money is given by the Diocese, the city and the department, and the Bishop, the Prefect and the Mayor keep a close eye on the evolution of the epidemic; donations in kind are sent daily and a lottery is organized by the Ladies of the Good Shepherd Association for the sick.

In Arras in the North of France typhoid affects tens of people and the house mourns four victims:

“Towards the end of October, typhoid fever began to strike our Monastery and, during four months, we had 60 to 70 sick. The administrators of the hospices took about 30 of them, providing them with the most thoughtful care; we are very grateful to them; but the public did not treat us so favourably and, according to his prejudices, we were not worth much… nothing was spared us… it was as if all hell had broken loose against us…

The Mayor and the Central Commissioner came to visit us on Sunday in order to reassure our neighbours. Mr Stival, our devoted doctor who feared neither efforts nor tiredness during these bad days, pleaded our cause; besides, these gentlemen saw the order of the house and even praised it. […] When we turned to our good Father Eudes we felt the joy revive in our hearts. We did a novena to him and promised to send 100 francs for the costs of the Introduction of his cause, and, from this moment, the tempest calmed down; the recoveries were quick and at Christmas all the convalescents were able to attend Mass; above all what was very happy is that nobody has had after-effects. We only had four victims, one in each group. During this trying time, His Lordship came to visit us twice. He did not forget our children who were in the Hospice. All the members of the Clergy always proved to be very devoted, as well as friends of the house.[14]”

Typhoid continued to rage during the first half of the 20th Century. In Rome during the First World War, in Portugal in 1937 in the community in Vila Nova de Gaia affected because of the flood of the Douro, and in Annonay in France in June 1948 when the Departmental Direction of Health gives some recommendations to the Superior following the contamination of four residents[15]: the rapid vaccination or re-vaccination of the whole house (people in care and Sisters), a bacterial analysis of the water, the automatic disinfection of the sanitation facilities.

The Spanish flu

The houses of the Congregation were not spared during this extremely severe pandemic throughout the world in 1918[16].

The noviciate and the classes were badly hit in Angers in August and in the autumn of 1918. Around 30 novices and between 50 and 60 young people in care fall ill. Six of the latter group die as well as several Contemplative Sisters.

In Ecully near Lyon, 9 people died in two weeks (an Apostolic Sisters, 4 Contemplatives and five residents) including 3 on the same day: “Such a hecatomb was never seen!”

At the St. Louis Gonzaga boarding school in Montreal (Canada), a single death occurred. All the day students had to be sent back to their families by order of the Central Health Bureau at the beginning of October 1918.

Tuberculosis and other diseases

A very common disease, tuberculosis continues to wreak havoc in the 19th Century including among the younger people. During the 1850s, the Sisters, malnourished, find it hard to resist to this plague which is often referred to as a “chest disease”. References to the illness appear from time to time in the letters of St. Mary Euphrasia, for instance about a Sister for whom the climate of Northern France proves pernicious: “Mary of St. Angela has been condemned by the doctors in Metz, who say she will never be able to live in the North, because of her chest (…).[17]”

Various diseases which can be related to the tuberculosis are mentioned in the archives, in rather undefined terms, like in the community in Arras in 1859: “In the month of October all kinds of illnesses paid a visit to the house; and in the space of two months our Sisters have had 16 invalid children, one of whom died (…).[18]”

Tuberculosis even increases at the middle of the 20th Century: between 1906 and 1918 France becomes the second country most at risk in Europe.

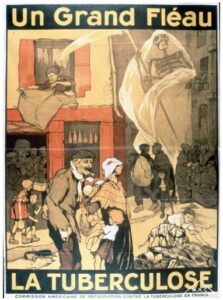

“A great evil. Tuberculosis”

Poster from a campaign of prevention between 1914 and 1918

Source: histoire-image.org

Other types of epidemics also affected the houses, for example a “throat disease known as flu” in Toulouse in 1837 which spreads in the whole town. At Our Lady of Charity, it starts with the young people in care before affecting the community. Eighty people are ill at a time, with one novice remaining valid. The dormitories of the residents are turned into infirmaries, and the Sister in charge of the kitchen is obliged to prepare broths and “cauldrons of herbal tea”. The Sisters recover but several young people in care die.

Conclusion

Epidemics struck regularly and more or less severely in the last centuries, paralysing the life of the community, requiring adjustments supported by the authorities. In the case of serious epidemics, the fear of contagion sometimes led to the quarantine of the sick.

This account is based on information from the archives in Angers. The same phenomenon must have happened in other countries. It teaches us that throughout the history of our world, as in our Congregation, there were a great many epidemics. When today we live with coronavirus, this global plague takes another dimension through the communication networks. We are immersed into this atmosphere.

With an epidemic obviously comes death. It creates fear and an anxiety for the future. But man has always demonstrated resilience together with a strong wish to defeat these epidemics and to live in believing in the future. This is possible provided we trust in the human capacity to face it. In this time of crisis, it is necessary to fight evil so as to develop remedies, vaccinations still unknown today.

In our Congregation, we are witness to the fact that nothing prevents the Sisters from pursuing their mission. Even in the face of death, there are other Sisters who volunteer to strengthen the mission. St. Mary Euphrasia even dared to use the means of communication of her time to keep the links with the Sisters of the other communities. We can say that the vow of zeal which motives us and drives us to live in Hope whatever the circumstances, even the most difficult ones, remains our strength, today like yesterday!

In our Communities throughout the world Sisters became victims of Covid-19. However, Sisters all over continued their mission: to join the most destitute, those who are most affected in this time of crisis while observing the sanitary rules imposed in each country.

Each period of crisis passes by and brings creative initiatives. In the end, are we able to say that “a new world is rising”? A fraternal world in which people stick together, a world of hope, in which the goodness present in the heart of every human being could become a source of life.