We take a stand against the culture of violence against women

By Fiorella Capasso,Fiodanice-Cultures en dialogue

December 2020-January 2021 – part 2

We take a stand for the feminine. This is the key, spotted in the mist[1], that violence against women drops on us, both if we look at traditional cultural contexts —a dominant patriarchy, even if tempered by globalization—and if we admit what is going on in our Western world:

—a dominant patriarchy, even if tempered by globalization—and if we admit what is going on in our Western world:

“Today, the twilight of the patriarchy is not leading to a society with more feminine characteristics, which is supposed to be more attentive to relationships and feelings. The post-modern and post-patriarchal world is not post-masculine at all. Instead, it emphasizes the pre-paternal qualities of the male: those of a fighter (against competitors), of a hunter (of females, but also of success and profit, demanded from an increasingly competitive economic life)” [2].

The end of the patriarchy is dreading the multimillennial human organization in terms of both interpersonal relations and living-in-society at its core, that is, how society forms and endures: a mechanism so rooted that it looks as if it has always been part of the natural order of things.

The end of the patriarchy is dreading the multimillennial human organization in terms of both interpersonal relations and living-in-society at its core, that is, how society forms and endures: a mechanism so rooted that it looks as if it has always been part of the natural order of things.

This epochal change, while it seems to free both men and women from tangled structural, socio-cultural and interpersonal ties, actually exposes them to an unprecedented complexity characterized by confusion, uncertainties, ambiguity and dragged-out conflicts that often become sources of violence.

We live in an era dominated by the rational discourse of science and, above all, by the discourse of financial capitalism. The world, governed by a technocratic paradigm[3], turns at “too fast” a pace, so that it hides reality from us. Where will we end up, exhausted[4] and caught in a pervasive and fragmented cultural and structural inertia charged with rage and resentment, almost deprived of the ability to resonances, to feel ourselves, and the other?[5] In times of crisis and transformation, women are always burdened with a symbolic and practical overload of demands and pretensions.“[…] I wanted to ‘be’. And he ‘forgave’ my being alive!”[6].

The twilight of patriarchy also corresponds to the collapse of the father figure, summarized in a metaphor that in the last few years has become of common use, the evaporation of the father[7]. He is going from being a blesser to just being a benefactor turned into a ‘male mother’[8], often “used to counting money ‘for’ the life of his child, but to counting less and less ‘in’ their life”[9]. The fear that the patriarchy will drag institutions that are still fundamental to the most basic social order into its downfall, thus causing chaos, reactionary responses, or resistance, is well-founded.

In situations of conflict where the father figure evaporates and the male figure prevails, the children themselves can become direct victims of that violence, while the witnessed one, the invisible one, is always there, it is contextual, you can’t see it, but you do feel it! Sometimes the ultimate gesture is “mediated”: even though the victim is the mother, the father ruins the life of his children “only”, and then puts an end to his own existence too. “It’s not an uncontrolled impulse. They want to punish the mother and reaffirm their masculinity”, experts state[10]. But it is also true that, on the women’s side, especially in the family/affective sphere, we come across a sort of unreasonableness for which “many murders are made possible because of the unbearable surprise generated by the discovery of the other side of the person who, not only did we love, but loved us back too. Neither too much nor too little. Calculations are useless and misleading. Neither women nor men love too much. ‘Too much’ belongs to a certain something that inhabits even the most sincere love, indeed, it is precisely because of this ‘something’ that love can seem extraordinary and unique”[11] …so absolute and unrenounceable that we cannot let it go in time and/or without granting him a last chance, or her a last clarification, but—as the news often tells us—it is actually more likely to become a last appointment with physical and symbolic life, both overwhelmed by their respective legacies and mists.

while the witnessed one, the invisible one, is always there, it is contextual, you can’t see it, but you do feel it! Sometimes the ultimate gesture is “mediated”: even though the victim is the mother, the father ruins the life of his children “only”, and then puts an end to his own existence too. “It’s not an uncontrolled impulse. They want to punish the mother and reaffirm their masculinity”, experts state[10]. But it is also true that, on the women’s side, especially in the family/affective sphere, we come across a sort of unreasonableness for which “many murders are made possible because of the unbearable surprise generated by the discovery of the other side of the person who, not only did we love, but loved us back too. Neither too much nor too little. Calculations are useless and misleading. Neither women nor men love too much. ‘Too much’ belongs to a certain something that inhabits even the most sincere love, indeed, it is precisely because of this ‘something’ that love can seem extraordinary and unique”[11] …so absolute and unrenounceable that we cannot let it go in time and/or without granting him a last chance, or her a last clarification, but—as the news often tells us—it is actually more likely to become a last appointment with physical and symbolic life, both overwhelmed by their respective legacies and mists.

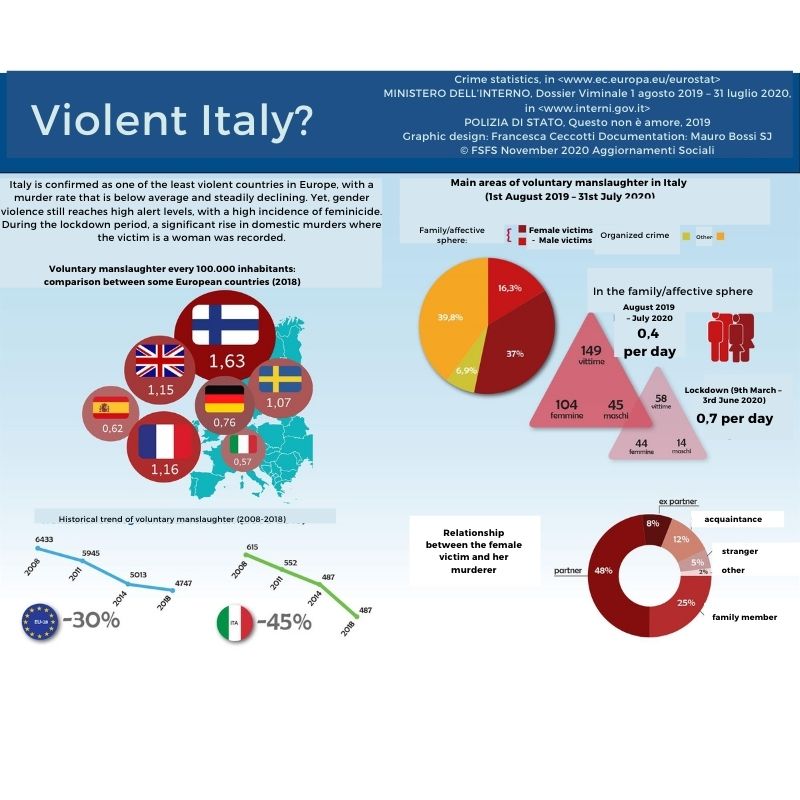

Yet recent data[12] indicate that Italy remains among the least violent countries in Europe, with homicide rates much below average and constantly decreasing. The historical trend of voluntary manslaughter over the last ten years (2008-2018) has declined by 45%, compared to a European average of less than 30%. Unfortunately, gender violence remains at high alert levels and has a high incidence of feminicides in the family/affective sphere (about 70%), with a rate of 0.4 victims per day, which almost doubled during the first lockdown period: giving death is an illusory way to get rid of hatred – and of the perverse attachment that derives from it – towards the other. A vile attempt of mastering one’s own powerlessness”[13].

Yet recent data[12] indicate that Italy remains among the least violent countries in Europe, with homicide rates much below average and constantly decreasing. The historical trend of voluntary manslaughter over the last ten years (2008-2018) has declined by 45%, compared to a European average of less than 30%. Unfortunately, gender violence remains at high alert levels and has a high incidence of feminicides in the family/affective sphere (about 70%), with a rate of 0.4 victims per day, which almost doubled during the first lockdown period: giving death is an illusory way to get rid of hatred – and of the perverse attachment that derives from it – towards the other. A vile attempt of mastering one’s own powerlessness”[13].

These are dark times[14] of dense mist, if even authoritative sources provide gray, reductive and misleading visions. Witnessed violence (which violates children’s lives even when it spares their bodies), inevitably associated with domestic violence, is not even mentioned! But it is pure violence, as invisible as it is reproducible and contaminates the future, from generation to generation. The question mark in the title, “Italia violenta?” [Violent Italy?], is shocking. It almost seems to suggest that because the wide majority of Europe’s largest countries are in a worse situation than us…then we might be good. Are we maybe facing a new version of the banality of evil?

These are dark times[14] of dense mist, if even authoritative sources provide gray, reductive and misleading visions. Witnessed violence (which violates children’s lives even when it spares their bodies), inevitably associated with domestic violence, is not even mentioned! But it is pure violence, as invisible as it is reproducible and contaminates the future, from generation to generation. The question mark in the title, “Italia violenta?” [Violent Italy?], is shocking. It almost seems to suggest that because the wide majority of Europe’s largest countries are in a worse situation than us…then we might be good. Are we maybe facing a new version of the banality of evil?

Stop turning the spotlight on this social scourge on November 25[15] only!

Or only when—about every three days—a woman is killed by her partner or ex-partner, thus signaling also a vast, disturbing and painful “buried” part!

Let’s stop[16]! Let’s open our eyes in front of these harrowing scenarios despite, as we know…”’Twas better—the perceiving not”[17].

Let’s walk through this fear of being petrified[18] by horror! Are we so incapable of bearing powerlessness[19]?

The cry “Not one woman less!” [20] is true to us also in harmony with the spiritual and planning heritage of the Congregation: for St Mary Euphrasia (link alla vita), “a soul is worth more than the world”.

Fortunately, the European Court of Human Rights, back in 2017, has taken a critical look at Italy because of the lack of protection for victims of violent crimes on women[21]. In 2018, the Italian Superior Council of the Judiciary, after admitting the “dramatic resurgence of events related to this area [Ed. the area of gender and domestic violence] which now represent a true national emergency”[22], started “a procedure aimed at drawing up guidelines and disseminating good practices related to lawsuits in the areas of gender and domestic violence, also with a view to aligning jurisdictional intervention in this field with supranational standards.” An explicit reference is made, in particular, to the Istanbul Convention on domestic violence (2011): the first legally binding instrument that creates “a comprehensive legal framework and approach to combat violence against women” as a violation of human rights, and focuses on the prevention of domestic violence, the protection of victims and the prosecution of perpetrators.

on women[21]. In 2018, the Italian Superior Council of the Judiciary, after admitting the “dramatic resurgence of events related to this area [Ed. the area of gender and domestic violence] which now represent a true national emergency”[22], started “a procedure aimed at drawing up guidelines and disseminating good practices related to lawsuits in the areas of gender and domestic violence, also with a view to aligning jurisdictional intervention in this field with supranational standards.” An explicit reference is made, in particular, to the Istanbul Convention on domestic violence (2011): the first legally binding instrument that creates “a comprehensive legal framework and approach to combat violence against women” as a violation of human rights, and focuses on the prevention of domestic violence, the protection of victims and the prosecution of perpetrators.

Italy was among the first nations to ratify it (2013), but its impact on this “national emergency” is still minimal, as pointed out by the Superior Council of the Judiciary itself in its 2018 Resolution. In this matter, the gap between formal and concrete levels risks becoming an abyss for the ethics of good intentions and, above all, a legal vacuum in which broken lives will pile up. Not only those of women and children, but of all the unfortunate protagonists of events in which personal vulnerabilities intertwine with the structural contradictions in the relationship between man and woman: “Personal biographies cannot go against structural contradictions”…experts notice[23].

Italy was among the first nations to ratify it (2013), but its impact on this “national emergency” is still minimal, as pointed out by the Superior Council of the Judiciary itself in its 2018 Resolution. In this matter, the gap between formal and concrete levels risks becoming an abyss for the ethics of good intentions and, above all, a legal vacuum in which broken lives will pile up. Not only those of women and children, but of all the unfortunate protagonists of events in which personal vulnerabilities intertwine with the structural contradictions in the relationship between man and woman: “Personal biographies cannot go against structural contradictions”…experts notice[23].

To date, the critical aspects of initiatives to combat violence against women largely prevail over the positive ones[24]. The legal and logical-rational approach is increasingly proving to be a necessary but not sufficient condition, not only in terms of prevention[25]. Violence against women, especially in the family/affective sphere, is in fact an issue that does not concern only Justice[26]; it cannot be reduced to the discourse of “possession” of one over the other and is not enclosed in a Truth, the truth of Good or Evil.

The mist surrounding the question of gender, domestic and witnessed violence is still dense. To venture into it requires prudence, audacity and a climate of social friendship[27]: it is urgent to engage, each one of us, in a new moral imagination[28] to advocate over time, from generation to generation.

of social friendship[27]: it is urgent to engage, each one of us, in a new moral imagination[28] to advocate over time, from generation to generation.

The unconsciously constrictive legacies which—as we suggested in the first part—are “handed over” at the time of birth to girls and boys, are omens of potential tragedies. But each new generation, if given the time, can contribute to the liberation from these constraints, which—in the sphere of violence against women—sometimes appear inescapable, like monsters that devour energies, dreams, local, national, European and international treaties, frustrating the attempts that, in the public sphere and in civil society, are incessantly being made to overcome violence against women as women and against children:

The unconsciously constrictive legacies which—as we suggested in the first part—are “handed over” at the time of birth to girls and boys, are omens of potential tragedies. But each new generation, if given the time, can contribute to the liberation from these constraints, which—in the sphere of violence against women—sometimes appear inescapable, like monsters that devour energies, dreams, local, national, European and international treaties, frustrating the attempts that, in the public sphere and in civil society, are incessantly being made to overcome violence against women as women and against children:

“Transmission is not a one-way movement. Unlike History, transmission is always a bilateral operation, a work of relationship, extracted from life. It is not about transferring an object from one hand to another. It requires a double action: by the person who transmits and by the person who receives the transmission. It does not work under compulsion. Caught in the game of generations, [the transmission] has to do with the wishes of both the old ones and the new ones. It is the new generations that determine whether they want it and why do they find interest in that heritage. The old ones are asked to listen to the request, to move their language towards another one […]. History does not proceed by addition, but by restructuring” [29].

As far as we are concerned, for the moment, we have been able to glimpse that taking a stand for the feminine has to do especially with the capability to bear the feminine[30] and with the negative capability[31], both of which are necessary—before, during and after every planned intervention, which would otherwise be vain—to contain “an unprecedented sadness”, “that black sun”[32] that would rise over the sky of feminine reflection at the end of patriarchy. And it has to do with the experience of the limit: the most deserted of our time and mother of the greatest current crises, from the Coronavirus to the climate emergency. An experience that always turns out to be challenging and imperfect—like everything pertaining to love—but necessary, to re-open paths to one’s own life, that of the other and with the other, while keeping an eye on the world that we will hand over to future generations: “And so, love makes one transit, come and go between antagonistic areas of reality, penetrates them and discovers its non-being, its hell…it destroys and for the same reason gives birth to consciousness, being, as it is, the full life of the soul…”[33].

the feminine[30] and with the negative capability[31], both of which are necessary—before, during and after every planned intervention, which would otherwise be vain—to contain “an unprecedented sadness”, “that black sun”[32] that would rise over the sky of feminine reflection at the end of patriarchy. And it has to do with the experience of the limit: the most deserted of our time and mother of the greatest current crises, from the Coronavirus to the climate emergency. An experience that always turns out to be challenging and imperfect—like everything pertaining to love—but necessary, to re-open paths to one’s own life, that of the other and with the other, while keeping an eye on the world that we will hand over to future generations: “And so, love makes one transit, come and go between antagonistic areas of reality, penetrates them and discovers its non-being, its hell…it destroys and for the same reason gives birth to consciousness, being, as it is, the full life of the soul…”[33].

To bear the view of the disturbing landscape of violence against women, for their being women, I was helped by the image of the “red sun” by Maria Lai[34], the first artist to create, with needle and thread, relational artworks involving different people and territories. Maria, with her humble and wise art, weaves landscapes and languages. Another Mary comes to mind, the Mother who “treasured up all these things and pondered them in her heart.” (Luke 2:19).

To bear the view of the disturbing landscape of violence against women, for their being women, I was helped by the image of the “red sun” by Maria Lai[34], the first artist to create, with needle and thread, relational artworks involving different people and territories. Maria, with her humble and wise art, weaves landscapes and languages. Another Mary comes to mind, the Mother who “treasured up all these things and pondered them in her heart.” (Luke 2:19).

I believe that this is, from the point of view of values and in theoretical-methodological terms, the feminine perspective towards which it is appropriate to move in the strategic fight against violence against women and children: to move towards renewed landscapes and languages, in order to co-invent and realize them, over time, with an humble and wise art more capable of generating and preserving history and more fertile stories. Our generation could weave the first chapters, as the result of many handcrafted strategic-territorial-nonviolent plans, of pacts without swords[35], activators of both inclusive and open processes: interconnected and enhancing the cognitive and social capital produced by initiatives to combat violence against women, in progress and past.

Holding the sun by the hand , we will thus try to untangle the tangled threads of Pollock’s painting and, perhaps, we will be able to weave Convergences created by harmonies and synergies[36].

by harmonies and synergies[36].

By cooperating across different link a genders and generations, valuing their differences, we will contribute, women and men together, in connection with public institutions and civil society actors—at local, national and European level—to eliminate visible and invisible violence…at least from the lives of women, girls and children.

It is the business[37] of several generations committed to inventing and practicing forms of coexistence more respectful of the dignity of each and every one, to then transmit from birth, right from the cradle.

By holding the sun by the hand we will prepare times in which today’s mist will be more bearable. It will be less frequent and only sporadic. These will be the times that the poet, as is proper to him, had already foreseen:

By holding the sun by the hand we will prepare times in which today’s mist will be more bearable. It will be less frequent and only sporadic. These will be the times that the poet, as is proper to him, had already foreseen:

In the dawn, armed with a burning patience,

we shall enter the splendid cities[38].