We take a stand for the mysterious awakenings to responsibilities

By Fiorella Capasso,Fiodanice-Cultures en dialogue

May2020

Even if we don’t will it, God matures[1]. These words – together with one of the most significative reflections of the Foundress, Saint Mary Euphrasia, “This is as the mysterious work of a hive, where each occupied herself for the general good.” – offer us a magnifying glass on what is happening in our apostolic realities committed to peace, economic justice and integral ecology while welcoming migrants, women and girls in distress, sometimes exposed, with kids, to human trafficking and sexual and labour exploitation.

New looks are needed to open heart and mind to the understanding of the anguishes of women in distress, often even child brides, welcomed with their children. By us they are called to take on a sort of personal, more integral and integrated mission: to share, in unexpected ways, the growth of the life they have generated. It was not enough to give birth to them, the children, they must once again give them life, giving their children and themselves back to life and to the co-construction of a future that is not an unfortunate repetition of the past, from generation to generation. But “the woman and God have a secret of their own which Adam (depicted sleeping) will never come to grips with” highlights a theologian[2], very dear to Italian devoted people, commenting on the creation of Eve in Christian art. And isn’t the mission rooted in this “secret” requested from all women who become mothers? Like from the Mother of all, “she who conceals a thousand roads”[3]?

The women who come “to us” are called Insaf, Arbia, Amira, Mounia, Vesna, Mila, Rajia, Hiba, Svetlana, Aishani, Faith, Fatimah, but also, Sara, Ada, Valeria, Adriana, Federica, Luana, Alice, Mara ecc. They come from a thousand roads, mainly Italian, Romanian, Kosovan, Moroccan, Nigerian, Ivorian, Burkinabé, Bengali. They conceal incomparable worlds and experiences. They speak unknown languages and idioms that convey values, concepts and the meaning of the life they received, foreigners to “us” and between “them”.

The women who come “to us” are called Insaf, Arbia, Amira, Mounia, Vesna, Mila, Rajia, Hiba, Svetlana, Aishani, Faith, Fatimah, but also, Sara, Ada, Valeria, Adriana, Federica, Luana, Alice, Mara ecc. They come from a thousand roads, mainly Italian, Romanian, Kosovan, Moroccan, Nigerian, Ivorian, Burkinabé, Bengali. They conceal incomparable worlds and experiences. They speak unknown languages and idioms that convey values, concepts and the meaning of the life they received, foreigners to “us” and between “them”.

They often jealously guard their values, as if to make them inaccessible; instead sometimes they seem to hurriedly get rid of them, like they’re ashamed of them. But perhaps those are just ways to protect them and protect themselves from comparison with diversity: they are afraid of finding themselves stuck in dynamics of devaluation and/or domination with which they have a sinister familiarity. Perhaps this is the reason why, many of them, and for so long, refuse to acknowledge that, by doing so, they risk losing their original vital identity traits. It seems difficult and very painful to accept the fact that keeping one’s roots locked up or, on the contrary, getting rid of them quickly means building one’s own future and that of their children on the sand. Even more difficult appears emancipating and going beyond life projects that were born for the need of “freedom from” familiar, social and cultural hierarchical logics that have trampled on dreams and dignity. They struggle to distinguish constraints from obligations: they do not know that the first ones create generative bonds, while obligations chain dreams and stifle the “freedom to” desire [4] and live what’s new. Without roots, without the recognition of one’s own specificity, one can only survive and make one survive. Roots like life, they need breath and horizons, they cannot be frozen, trampled on or pulverized. Life must be spread around and fed in order for us to be fed with it… even when circumstances are frightening and seem adverse.

They are injured, vulnerable women in precarious socio-economic conditions. Many, especially foreign ones, are on the run, sometimes catapulted by traditional patriarchal systems of which they still own, deep down, the slow pace. This makes them appear, even in the eyes of their children, clumsy and unreliable because they are unable to equip them to move in this convulsive Western system of ours that has lost the ability to feel the other and the world… with the inhumanities that are in the public eye and with Nature rebelling against mistreatment and exploitation.

are on the run, sometimes catapulted by traditional patriarchal systems of which they still own, deep down, the slow pace. This makes them appear, even in the eyes of their children, clumsy and unreliable because they are unable to equip them to move in this convulsive Western system of ours that has lost the ability to feel the other and the world… with the inhumanities that are in the public eye and with Nature rebelling against mistreatment and exploitation.

We see them arrive, mistrustful and disoriented, with a life still arising in their womb, with babies clutched to their chest, almost like a shield, with frightened, tired [5] and/or angry little children clinging to their clothes, while the older ones wander with restless and elusive looks. They have stories of wandering soaked in emptiness and excess, of abuse and oppression, of deceits and self-deception, of almost unbridgeable lacks that expose them to old and new forms of dependence and submission both in love relationships and in the adherence to consumerist models of life that increase discomfort, dissatisfaction, demands and feelings of perennial inadequacy.

They come “to us” mostly forced by the Law, by decree of the Juvenile Court which entrusts children to Social Services: upstream, more and more often, there are reports of disturbances in the relationship with children of one or both parents and/or violent clashes in the relationships that have also compromised the exercise of parental responsibilities.

The Law bursts into their lives when it becomes necessary to avoid the risk of family dynamics that are harmful  for themselves and/or their children; when parenting is lived only as a private experience; when it is necessary to re-establish “positively” asymmetrical adult-child educational relationships, in which one of the two (the adult) takes on the burden of getting in tune with the other (the child), with no quid pro quo! “They come through you, but are not yours. And even if they live with you, they do not belong to you” [6].

for themselves and/or their children; when parenting is lived only as a private experience; when it is necessary to re-establish “positively” asymmetrical adult-child educational relationships, in which one of the two (the adult) takes on the burden of getting in tune with the other (the child), with no quid pro quo! “They come through you, but are not yours. And even if they live with you, they do not belong to you” [6].

By us the welcomed women, both Italian and foreign (and their partners when it is possible) are then forced to confront themselves with unknown educational principles, due to their culture of origin and/or personal experience of deprivation: children who in the first years of life have been “seen” and invested with trust, tomorrow will be in turn ready to invest trust in their peers, in the institutions and, above all, in themselves. On the contrary, the lack of trust will produce not only and not simply distrust, but distressed orientations, sick strategies and bad community relations. Hospitality without “ownership” must characterize the mother, just as responsibility without ownership must characterize the father [7].

How much strength we see coming out of the women who come “to us”! Let’s watch them with wonder as they advance and, though unprepared, take up the challenge of responsible parenting. They try to assume maternal and paternal functions as they try to transform the clashes with their partners into manageable conflicts between adults who avoid unloading them on the children’s shoulders. “God always begins with women, always. They open ways… May the Lord give us the courage that women have” [8].

advance and, though unprepared, take up the challenge of responsible parenting. They try to assume maternal and paternal functions as they try to transform the clashes with their partners into manageable conflicts between adults who avoid unloading them on the children’s shoulders. “God always begins with women, always. They open ways… May the Lord give us the courage that women have” [8].

How much tenacity, courage, patience, ability to forgive themselves and the others, to tolerate disorder, to look to the future (even when the future is not even in sight) is required from them, especially when they face the most agonizing questions: is it really true that my children are already dealing with a wounded childhood [9] and that, when they grow up, they will be confronted with a past of trampled dignity, caused by my frailties too, in addition to an absent and/or violent father? And again: are my children already living the same torments of my childhood? “That is why I must tell you what is horrible to know: it is within your grace that my anguish is born” [10].

Between sufferings and sudden little joys, these women go through crises that even in their eyes turn out to be paradoxical opportunities. They gradually discover, to their amazement, that the Law “allows a human being to be human”[11] and that, by prescribing restrictions and rules, creativity…of limits can awaken. For when I am weak, then I am strong (2 Corinthians 12-10)! It starts soon, by us the time of “never again as before” that today is (finally) in tune with what is happening “outside”, in the world of inequalities that Coronavirus turned upside down. The Pandemic is a tile of the environmental disaster: the virus has used globalization against us, and we need to invent together a totally different, more responsible, just and supportive system that widely promotes the transition from ethics of intentions to ethics of responsibility. Let’s open ourselves to the awareness of the consequences of our actions and let’s grow personal and collective reparative abilities: this is also the main message of the Green Encyclical, Laudato Si’, by Pope Francis.

The women who come “to us” fully participate in the awakening to responsibilities that is announced worldwide: they start from their daily life, from the multi-ethnic cohabitation with other welcomed women and children: from forced cohabitation they commit themselves to make it a strength! For the Italian and foreign women who have come “to us”, their new start is already underway! “Where the danger is, also grows the saving power”… says the poet [12]. Everything is uncertain, but not everything is lost [13].

The women who come “to us” fully participate in the awakening to responsibilities that is announced worldwide: they start from their daily life, from the multi-ethnic cohabitation with other welcomed women and children: from forced cohabitation they commit themselves to make it a strength! For the Italian and foreign women who have come “to us”, their new start is already underway! “Where the danger is, also grows the saving power”… says the poet [12]. Everything is uncertain, but not everything is lost [13].

They inspire deep respect, tenderness and esteem. We support them when they stumble as they mature and equip themselves for a life freed from painful submissions; they rhythm their relationship with their children in moments of closeness/separation in order to be able to enter – often for the first time – the labour market. We continue with reasoned enthusiasm to activate, with them and around them, alliances and territorial resources so that the times of the “mysterious work” of transformation are congruous and the supports made available are flexible and articulated: always inspired by the pedagogical principle of St. Mary Euphrasia, unheard of for her time and still today precious and prophetic: “Enhance them in their own eyes”. Alongside them we affine our accompanying skills, and for this reason, we associate responsibility with the ability to mature responses to direct and indirect, institutional and organizational mandates interwoven with an empathic management of aid relationships. “Knowing oneself and others is the most intense way of being responsible” [14].

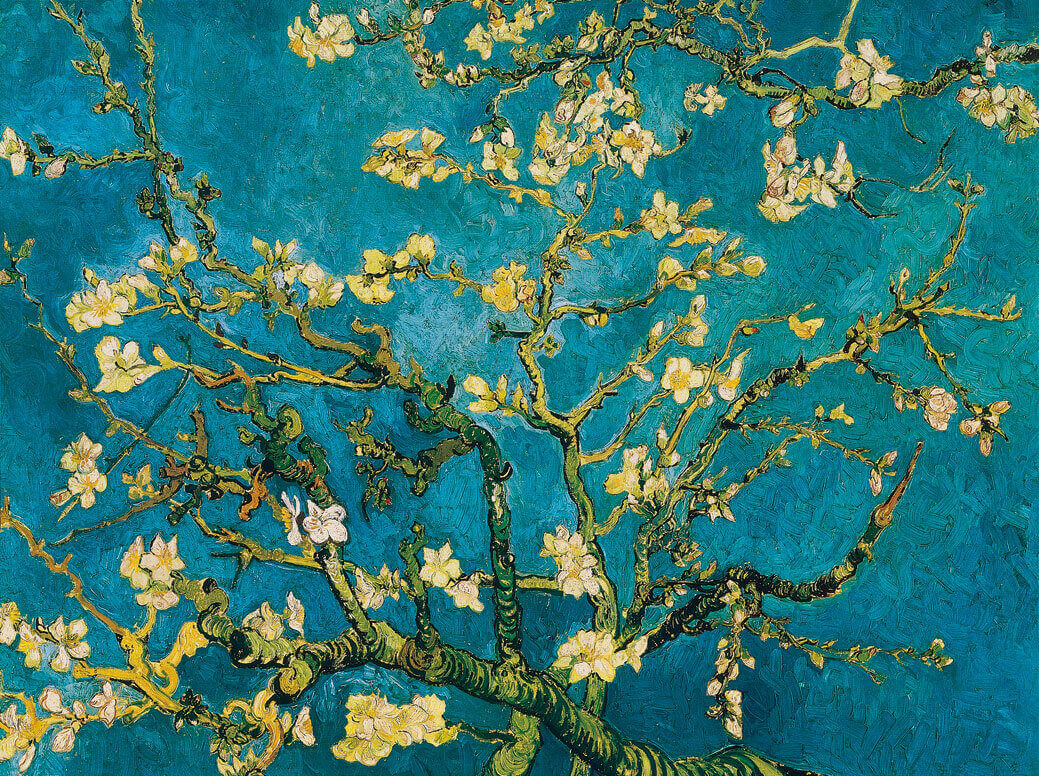

What a marvel the flowering almond tree branch painted by Van Gogh on the occasion of the birth of his grandson! The women who come “to us” look like the flowering almond tree: in Scripture it is a symbol of life, despite a winter landscape marked by death. Since its flowering is precocious, the literal meaning of the Hebrew word for almond tree is appropriately “one that awakens”. But in the biblical episode concerning the prophet Jeremiah’s vision of a bud, or branch, of almond tree, in addition to the announcement of the “awakening” we also find a second message: God’s faithfulness to His work. God is faithful, he never tires or sleeps: “For I am watching to see that my word is fulfilled” (Jeremiah 1:11-12). Responsibility is also faithfulness to life.