We take a stand for A special year of Laudato Si’ because everything is connected

By Fiorella Capasso,Fiodanice-Cultures en dialogue

Summer 2020

Everything is connected. Like a mantra, in recent weeks, this truth has resonated from many places in our communities thanks also to the four webinars, Conversations at the time of the Coronavirus [1], animated from India by Brother Philip Pinto who spoke to the apostolic realities of the five continents evoking the beauty and complexity of the links between cosmological spirituality and the current formation process which requires four approaches: Experience, Participation, Contemplation and Connection.

In continuity [2] with the session “Love, the Heart of the Universe” held in 2018 at the Mother House in Angers, Brother Pinto indicated the new perspectives that are beginning to emerge and transform our faith, thanks to the integration of science and theology, with consequences on the formation processes that are constantly being adapted to the complex and rapidly changing world in which we live: “The greatest challenge today is to broaden our field of reflection, to allow new wisdom to emerge and reshape our image of God, our understanding of faith and the world, and to rethink our way of living religious life so that it may be relevant in the future”.

Everything is connected… a mantra that we have often heard in recent months, in the midst of the devastating Coronavirus event. The pandemic acted as a catalyst for economic, social and cultural dynamics and their contradictions. It did not introduce radically new elements, but made repercussions visible earlier than expected and revealed what before remained more easily hidden or implicit, even if the most attentive observers had already pointed it out: “The storm exposes our vulnerability and uncovers those false and superfluous certainties around which we have constructed our daily schedules.” [3]

Everything is connected… a mantra that we have often heard in recent months, in the midst of the devastating Coronavirus event. The pandemic acted as a catalyst for economic, social and cultural dynamics and their contradictions. It did not introduce radically new elements, but made repercussions visible earlier than expected and revealed what before remained more easily hidden or implicit, even if the most attentive observers had already pointed it out: “The storm exposes our vulnerability and uncovers those false and superfluous certainties around which we have constructed our daily schedules.” [3]

We knew that work, home, environment and health were crucial points even before, just as we knew how contradictory, problematic, unjust and even potentially catastrophic some choices and behaviors were, both individual and collective. Did we think we would always “stay healthy in a world that was sick” [4]? In other words, what is happening to us is that we can no longer pretend not to see that the future that we were building with our actions and our choices, for us and for generations to come, in what today seems to us as our past, was unsustainable. This is the vision that has prevailed over the last few centuries: man, at the centre of the universe, has tried desperately to control everything while, instead, he has lost control of it.

unjust and even potentially catastrophic some choices and behaviors were, both individual and collective. Did we think we would always “stay healthy in a world that was sick” [4]? In other words, what is happening to us is that we can no longer pretend not to see that the future that we were building with our actions and our choices, for us and for generations to come, in what today seems to us as our past, was unsustainable. This is the vision that has prevailed over the last few centuries: man, at the centre of the universe, has tried desperately to control everything while, instead, he has lost control of it.

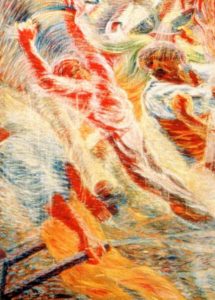

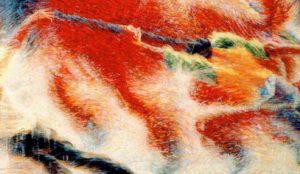

Paradoxical, but not unpredictable. The painting of the early twentieth century that we have chosen this month, The city rises, also expresses this effectively. The artist [5] wanted to fix the character of our industrial time that glorifies the myth of modern man as the creator of a new world. He takes his cue from a view of Milan from the  balcony of the house where he lived and transforms a normal moment of work, in an ordinary building site, into a celebration of the idea of industrial progress with its unstoppable advance. The horses, held in vain by men attached to the reins, are the dramatic symbol of this. In the whirlwind of colours we can see three of them: a white one on the left, another one dominating the middle of the painting, and one on the right. The latter two are coloured in red and have blue profiles on their rump that resemble wings. An omen of return to the primordial chaos of confusion and undifferentiation among living beings? Did the horses already evoke the fall of Icarus from the wings made of wax that concerns all of us today? How can we then be surprised by the fact that Milan – called the moral capital of Italy – is, in the whole world and together with New York, among the cities that today pay the highest price for the dynamism of modernity, the exaltation of technology, the new and the “dané” [6], in the whirlpool of epochal emergencies?

balcony of the house where he lived and transforms a normal moment of work, in an ordinary building site, into a celebration of the idea of industrial progress with its unstoppable advance. The horses, held in vain by men attached to the reins, are the dramatic symbol of this. In the whirlwind of colours we can see three of them: a white one on the left, another one dominating the middle of the painting, and one on the right. The latter two are coloured in red and have blue profiles on their rump that resemble wings. An omen of return to the primordial chaos of confusion and undifferentiation among living beings? Did the horses already evoke the fall of Icarus from the wings made of wax that concerns all of us today? How can we then be surprised by the fact that Milan – called the moral capital of Italy – is, in the whole world and together with New York, among the cities that today pay the highest price for the dynamism of modernity, the exaltation of technology, the new and the “dané” [6], in the whirlpool of epochal emergencies?

[…] we had to stop.

We knew it. We all felt

that our actions

were too furious. Staying inside things.

Out of our minds.

Shaking every hour – making it profitable. [7]

It is clear that we have to change, but it is even clearer that the real question is whether we want to, whether we can change.

Everything is connected. This was also the thread chosen by Pope Francis for the Laudato Si’ Week 2020 with a renewed call to “respond to the ecological crisis because the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor can no longer wait”. And so at the end of the week, on May 24th, five years after the publication of this encyclical on Integral Ecology, the Pope once again takes on his shoulders the weight of “speaking the truth in love” (Ephesians 4,15) – as he had already done at that memorable moment of prayer for the pandemic, on March 27, on St. Peter’s Square, empty as ever – and promotes a special year of Laudato Si’, an encyclical about caring for the common home, “a reflection which has been both joyful and troubling.” [8]

Everything is connected. This was also the thread chosen by Pope Francis for the Laudato Si’ Week 2020 with a renewed call to “respond to the ecological crisis because the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor can no longer wait”. And so at the end of the week, on May 24th, five years after the publication of this encyclical on Integral Ecology, the Pope once again takes on his shoulders the weight of “speaking the truth in love” (Ephesians 4,15) – as he had already done at that memorable moment of prayer for the pandemic, on March 27, on St. Peter’s Square, empty as ever – and promotes a special year of Laudato Si’, an encyclical about caring for the common home, “a reflection which has been both joyful and troubling.” [8]

I’ve seen a Man

saying

“no one is saved alone”

because

we are not alone

if we believe

in God

and His Salvation.[9]

To speak the truth in love – this is what the Pope asks us – following Jesus, to bring life and bring it to the full (John 10): “What kind of world do we want to leave to those who come after us, to children who are now growing up?”. [10] Speaking the truth in love sets things in motion: let us take the other person seriously, let us offer hospitality and share what matters with those before us. Speaking the truth in love does not conceal, but recognizes and treats conflicts with meekness and hope [11]. And it often makes one glimpse things not yet seen. Truth frees love from the incrustations that have solidified over time, focusing on the realities that make life authentic for all and everyone, without much embarrassment, fear and hatred.

Pope Francis must have taken literally the conviction of the poor man of Assisi, whose name he bears first among the Popes who preceded him: “Start by doing what’s necessary; then do what’s possible; and suddenly you are doing the impossible.” And he even went so far as to overcome Pope John XXIII in audacity, whose Pacem in terris was addressed to “all men of good will”. With the Laudato Si’, Pope Francis summons all the inhabitants of the Earth to face together problems that concern all living people and require responses on a global scale: it seems a Manifesto for the humanity of the 21st century, who risks remaining without a future. Perhaps this is why his wisdom had immediately prompted him to entrust the disruptive nature of this encyclical to the Holy Spirit: on May 24, 2015, Pentecost was celebrated, the descent of the Spirit and his gifts of wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety and fear of the Lord.

The ecology proposed by the Pope is integral [12] since environmental, social and human aspects complement each other: “Today, however, we have to realize that a true ecological approach always becomes a social approach; it must integrate questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor”[13]. In unusual harsh words, the Laudato Si’ contests the denial of climate change as an expression of veiled power interests. “Veiled”, because it is evident that people are not fighting for scientific truth, but rather to protect particular interests [14]. In the analysis and response to the climate issue, it is not the interests of the powerful that should prevail, but the need for global justice.

true ecological approach always becomes a social approach; it must integrate questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor”[13]. In unusual harsh words, the Laudato Si’ contests the denial of climate change as an expression of veiled power interests. “Veiled”, because it is evident that people are not fighting for scientific truth, but rather to protect particular interests [14]. In the analysis and response to the climate issue, it is not the interests of the powerful that should prevail, but the need for global justice.

Everything is connected. In the encyclical we find two paths, a spiritual one and a conceptual one: the first welcomes an ancient teaching found in different religious traditions, including that of the Bible, according to which “less is more” and that “encourages a prophetic and contemplative lifestyle, one capable of deep enjoyment free of the obsession with consumption” [15]. As for the conceptual path, open to complex visions and keys of interpretation, it is articulated according to the three well-known steps of seeing, judging and acting [16]: presentation of the global environmental problems, as diagnosed by science (Chapter I), interpreted in the light of the biblical message (Chapter II) and articulated in the broader context of the Pope’s sensitivity to globalization and the modern age (Chapter III). Chapter IV deals with ethical guidelines, and the next two chapters illustrate the reasons and principles of action.

Everything is connected. In the encyclical we find two paths, a spiritual one and a conceptual one: the first welcomes an ancient teaching found in different religious traditions, including that of the Bible, according to which “less is more” and that “encourages a prophetic and contemplative lifestyle, one capable of deep enjoyment free of the obsession with consumption” [15]. As for the conceptual path, open to complex visions and keys of interpretation, it is articulated according to the three well-known steps of seeing, judging and acting [16]: presentation of the global environmental problems, as diagnosed by science (Chapter I), interpreted in the light of the biblical message (Chapter II) and articulated in the broader context of the Pope’s sensitivity to globalization and the modern age (Chapter III). Chapter IV deals with ethical guidelines, and the next two chapters illustrate the reasons and principles of action.

This is the first time that a Pope speaks with such authority to the whole world, not about religious matters, but about so many problems of common interest for the continuity/quality of life on the Planet. He does so with lucidity and words full of hope [17]: “Let us sing as we go. May our struggles and our concern for this planet never take away the joy of our hope” [18].

A special year of Laudato Si’ can accompany us in repairing and equipping ourselves with new skills to build without destroying, for the common good, to make humanity grow in knowledge, justice, solidarity and the ability to coexist among different people. A new world must emerge, where we are more aware of our fragility and ready for unpredictability as a dimension of the life of humanity. With greater awareness of our belonging to an ecosystem, a new social progress could be born, a policy of empathy, a new friendship with nature, men and God.